Article published by The New York Times. Article written by Brian Seibert.

The company, belatedly celebrating its 75th anniversary, presented a program with works by Limón and Doris Humphrey and a premiere by Olivier Tarpaga.

Nicholas Ruscica, foreground, and the company in Limón’s “Psalm.”Credit.” Credit: Christopher Jones

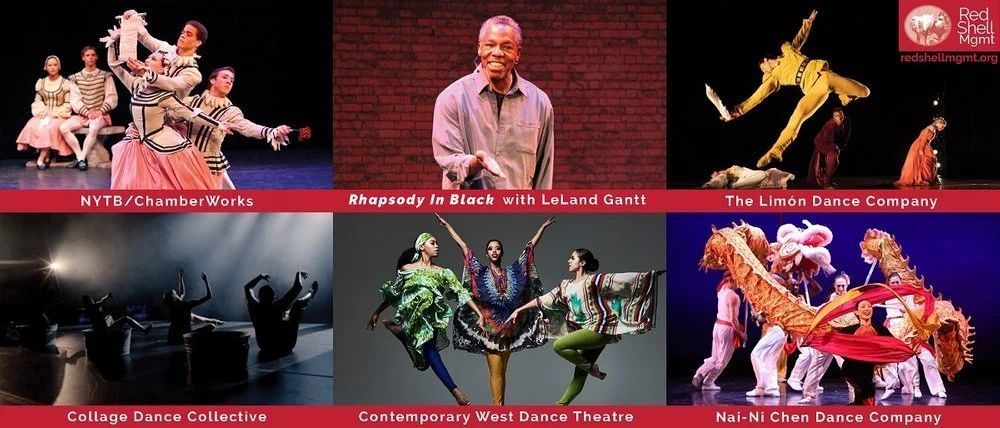

José Limón died in 1972. The Limón Dance Company, which he founded in 1946, lives on. On Tuesday, it returned to the Joyce Theater for a two-week run, a pandemic-delayed 75th anniversary celebration, under the new directorship of Dante Puleio. The first program (a second follows next week) accomplished the essential tasks: displaying a company in good shape, honoring the past without getting stuck in it.

That last part is tricky with Limón’s work, since the lofty tone and explicitly humanist themes can all too easily seem like an antiquated sermon. How to handle the threat of datedness? A legacy institution can’t avoid addressing history. Puleio has chosen to add narration, the voice of Dion Mucciacito prefacing each piece with context and quotes from Limón. This device gives the show the air of a public television documentary — informative, a little eat-your-vegetables — except that here, unlike in most documentaries, we get the dances in full.

At the start, we learn how Limón, migrating to the United States from Mexico, turned from painting to dance and learned about gravity and craftsmanship from Doris Humphrey, one of the mothers of modern dance. We hear about Humphrey’s discovery of falling, then we see her “Air for the G String” (1928), a dance of walking patterns in long capes that trail on the floor. In the fall of the fabric, we see the tilt and twist of Humphrey technique developing — the play of weight and lift that Limón made his own.

Before Limón’s “Psalm” (1967) — with its spare, insistent original score restored — we hear not only about how he based the dance on the Jewish legend of the 36 just men who sustain the world but how, when he made the work, he was dying of cancer. Thus, we are told, the dance is about the triumph over death and “one just man.” The weight of meaning is heavy; the smell of hagiography is high.

Perhaps for that reason, with each return of the work’s central dancer, identified in the program as “The Burden Bearer,” my heart sank. That’s no fault of Nicholas Ruscica, who danced the role well. But the anguish of that Christ figure, falling and borne aloft, is much less engaging than the motion of the ensemble: the angles, the elbows, the overlapping and massed forces. The formal power of Limón’s group choreography cuts through the sententiousness and martyrdom.

The second half of the program is less burdened. Limón’s “Chaconne,” a 1942 solo to Bach (played onstage by the violinist Johnny Gandelsman), is rich in feeling and form. Puleio has assigned it to a series of guest artists. Shayla-Vie Jenkins, on Tuesday, is certainly not a Limón dancer: too loose, too understated. But the interaction between her contemporary manner and Limón’s heroic style felt fresh with possibilities.

From left, Savannah Spratt, MJ Edwards and B. Woods in Olivier Tarpaga’s “Only One Will Rise.” Credit: Christopher Jones

Before Olivier Tarpaga’s “Only One Will Rise,” a premiere, the narration draws a connection between Limón’s immigrant experience and that of Tarpaga, who is from Burkina Faso. As the messianic title might indicate, Tarpaga (according to the narration) looks to “Psalm,” shifting focus from one just man to a “dark horse.” The dance has a central figure on a journey, MJ Edwards, a sinuous marvel of isolated body parts; the others lean away. But the work seems to be more about how everyone has shaking fits and falls down and could use a calming touch.

The music — an Afropop stew of percussion, bass and psychedelic guitar by Tarpaga and Tim Motzer — is played live. Never before has a Limón show been this funky. Picking up on Limón’s sharp elbows, the dancers jut them in rapid spirals around their heads, as if they had been beset by bees. At the end, Edwards looks up as the curtain falls. Very Limón.

Limón Dance Company

Through May 1 at the Joyce Theater; joyce.org.

Article originally published by The New York Times.